In his melancholic masterpiece Minima Moralia, the German philosopher Theodor Adorno famously declared, “Wrong life cannot be lived rightly.” ( “Es gibt kein richtiges Leben im falschen.”) Writing from the debris of World War II and the Holocaust, Adorno understood that individual morality is very hard to maintain within a structurally immoral and exploitative system.

Today, living in the much more interconnected world of global capitalism, this sentence haunts us with renewed vigor. We like to believe that the map of the world is now a collection of sovereign equals, that the age of empires has passed. Yet, if we apply the rigorous, critical lens of the Frankfurt School – looking not at the laws on paper, but at the phenomenology of power – we see that imperial hierarchies have not vanished. They have simply merged into the economic hierarchies, and the mass psychology, of capitalism. The imagery of Colonialism has been absorbed into what Adorno and Max Horkheimer termed the Culture Industry: a totalizing system of production that commodifies not just goods, but human relationships, identities, and perceptions. The colonial fracture operates today as a “myth” in the sense described by Ernst Cassirer: a constructed narrative that rationalizes the irrationality of economic and cultural domination.

The distinction between the “colonizer” and the “colonized” has been sublimated into a psychic constellation, a script of arrogance and anxiety that dictates how we speak, how we love, and how we dream. To understand this “Invisible Empire,” we must first map the ontology of the divide, the structural machinery that sorts humanity into Subjects and Objects.

The Anatomy of the Divide: A Diagnostic Overview

The distinction between colonizer and colonized cultures is defined by an ontological fracture in global society. It operates through three primary mechanisms that maintain the hierarchy long after the colonial administrators have left: Mobility, Representation, and Extraction.

- Mobility (The Subject vs. The Object): The most visible marker of the colonizer status today is the privilege of mobility without assimilation. When members of the dominant culture move to the Global South, they are linguistically codified as tourists or “expats.” This status implies voluntary movement, agency, and the right to remain culturally distinct. Conversely, when members of the Global South move to the Global North, they are codified as migrants or refugees. This status implies economic necessity and carries the burden of assimilation.

- Representation (The Viewer vs. The Viewed): The colonizer culture claims the position of the “Universal,” a neutral standard against which all others are measured. This manifests as “epistemic violence,” where non-Western knowledge is erased or reformatted to fit Western algorithms, and in media, where the “White Savior” trope ensures that even stories about indigenous liberation center on Western agency.

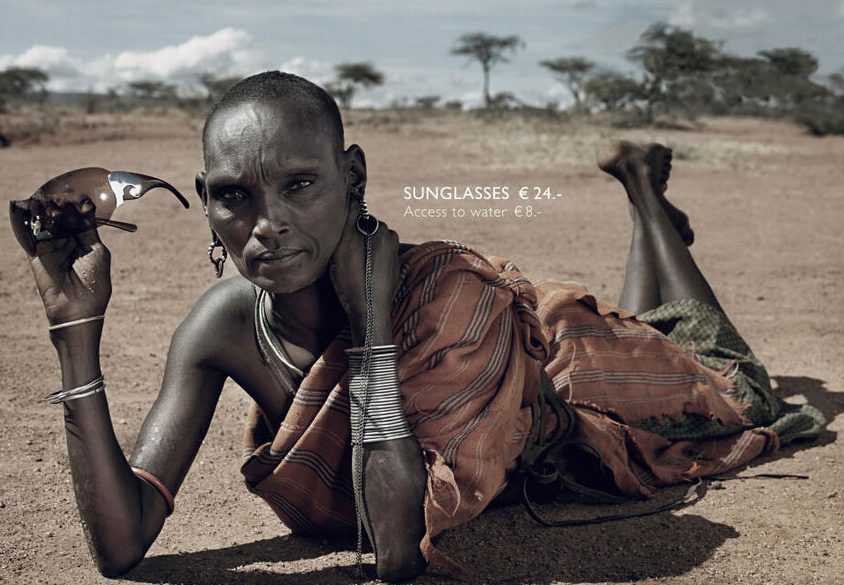

- Extraction (The Consumer vs. The Resource): Economically, the distinction is defined by the flow of value. Colonizer cultures view the colonized world primarily as a reservoir of raw material—whether that material is lithium for batteries, “authentic” experiences for tourists, factory workers in the Philippines, or “behavioral surplus” for AI training.

The Semantics of Domination

This structural divide is enforced first through language. Consider the asymmetry between the terms “Citizen” and “Refugee,” or “Expat” and “Immigrant.” From a purely functional standpoint, a British banker in Singapore and a Filipino nurse in London are engaged in the exact same activity: labor migration for economic gain. Yet, the Culture Industry assigns them opposing metaphysical statuses. The “Citizen” and the “Expat” are Subjects. He retains his individuality, his agency, and his connection to the “Metropole.” He is mobile, a “global citizen” whose presence is viewed as a gift to the host nation.

The “Immigrant,” conversely, is reified into an Object. She is stripped of her biography and reduced to a demographic statistic, a “flow,” or a “crisis.” As Adorno noted, the administrative mind seeks to classify in order to control. The label “Immigrant” serves to manage populations deemed surplus or threatening. This linguistic distinction is a sociological technology — a psychological force field that protects members of the colonizer cultures from an awareness of the “wrong life” they are living, allowing them to enjoy the surplus value of the Global South without acknowledging their complicity in its poverty.

The Architecture of Extraction: From Thao Dien to the Cloud

This psychic divide is etched into the very concrete of our cities and the code of our digital world.

In Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon), the distinction is spatially enforced. In the district of Thao Dien, we find the “Expat Bubble,” a sanitized enclave of international schools and avocado toast. Here, real estate is expensive, and the sensory reality of Vietnam is filtered out. The chaotic, organic noise of the city is replaced by the hum of air conditioning and soft music. This is in Walter Benjamin’s words “a phantasmagoria:” a dream world built to distract us from the means of its production. (The “phantasmagoria” borders on “Ideology:” in the words of Louis Althusser, “Ideology” is an individual’s imaginary relationship to the material conditions of their existence, or to the system of production in which they exist.)

Thao Dien offers the aesthetic of the colony (leisure, exoticism, service) without the guilt of the colonizer. Cross the river to District 4, and the phantasmagoria collapses into the visceral reality of density and survival. The Expat moves through this space not as a neighbor, but as a customer or a voyeur.

The extraction of value extends to the digital realm. We marvel at Artificial Intelligence as a triumph of Western science, but behind the screens of Facebook or ChatGPT lies a vast, invisible proletariat in the Philippines, Kenya, and Colombia. The tech factories, the call centers, or the workers who perform instrumental reason in its purest form: cleaning up the internet’s toxicity and labeling data to align algorithms with Western norms. This is epistemic violence: the colonized subject must prune away their own cultural context to train the machine, exporting the raw material of rationality itself while the value accumulates in Silicon Valley.

The Production of Mythology: Cinema

If the city provides the stage, the cinema provides the script. Hollywood functions as the primary carrier of colonial ideology, producing “mass deception” to resolve our structural guilt.

Consider the persistence of the White Savior trope in films like Avatar or Dune. These blockbusters ostensibly critique imperialism: they show evil empires destroying nature. Yet, they resolve this conflict through the figure of the White Messiah (Jake Sully, Paul Atreides). The indigenous people are depicted as “noble savages”—spiritually pure but politically impotent without the leadership of the white defector.

This narrative is a form of narcissistic reconciliation. It allows the Western audience to identify with the Good Colonizer who saves the day, absolving them of the crimes of the Bad Colonizer. It reinforces the deep-seated belief that agency is the exclusive property of the West, and that the “Other” exists only to facilitate the hero’s moral awakening.

Psychological Translation: Identity and Intimacy

Finally, let’s look at how this empire lives inside us. The colonial fracture is not just a political and economic system; it is a psychic constellation that shapes our identities.

- The Colonized Self (The Architecture of Shame): For the colonized subject, consciousness is defined by a “fissure.” Frantz Fanon called it a “nervous condition.” It manifests in the desire for skin whitening or the exhausting labor of “code-switching” in the workplace—flattening one’s accent and suppressing one’s culture to mimic the professional standards of the West. It is the anxiety of the imposter who fears their “native” inferiority will be exposed.

- The Colonizer Self (The Fragility of Narcissism): The “Expat” often relies on the reification of the local population to sustain their ego. In their home country, they may be average; in the Global South, their passport converts them into an elite. They may praise locals for being hard workers, simple, or welcoming, while these perceptions can be seen as patronizing compliments that reduce complex humans to sources of service.

- The Gendered Fracture: Nowhere is this clearer than in the “Passport Bros” phenomenon—Western men traveling to the Global South in search of “traditional” (submissive) women. This is a search for intimacy based on a fantasy where economic power guarantees romantic dominance. For the woman, it is often a calculated survival strategy. As Adorno might warn, love cannot exist between a Subject and an Object; as long as the relationship is transactional, it remains a form of colonization.

Conclusion: The Negation of the False

The distinction between colonizer and colonized is not a biological fatality, but a historical construction. It is a “dialectic of enlightenment” where technological progress is paid for by social regression.

- The Colonizer Culture is defined by the privilege of invisibility. It is the “Expat” who is never a migrant, the AI user who never sees the labeler, the moviegoer who sees himself as the hero. It is the false universal.

- The Colonized Culture is defined by the burden of visibility. It is the body that is policed, the mind that is mined for data, the culture that is appropriated for “local flavor.”

Is this distinction useful? Only if we use it not to stabilize these categories, but to explode them. We must recognize that the “freedom” of the digital nomad is built on the confinement of the worker without passport or visa. We need to realize that our beautiful and increasingly intelligent high-tech world is extracted from the minds of the marginalized.

To live “rightly” in this administered world is perhaps impossible. But to refuse the “myth,” to name the exploitation, and to look into the abyss of the fracture without blinking—that is the beginning of a true post-colonial consciousness. As Adorno warned, “The splinter in your eye is the best magnifying glass.” We must use that splinter to see the empire that hides in plain sight. We may not be able to dismantle the empire overnight, but by seeing it clearly, by refusing to be reconciled with the falseness of global consumerism, we carve out a space for what is true. How do we learn to recognize that the “Other” is not a backdrop, but a consciousness as vast and complex as our own?

Weblinks for further study:

Entries at the Stanford Encyclopedia for Philosophy