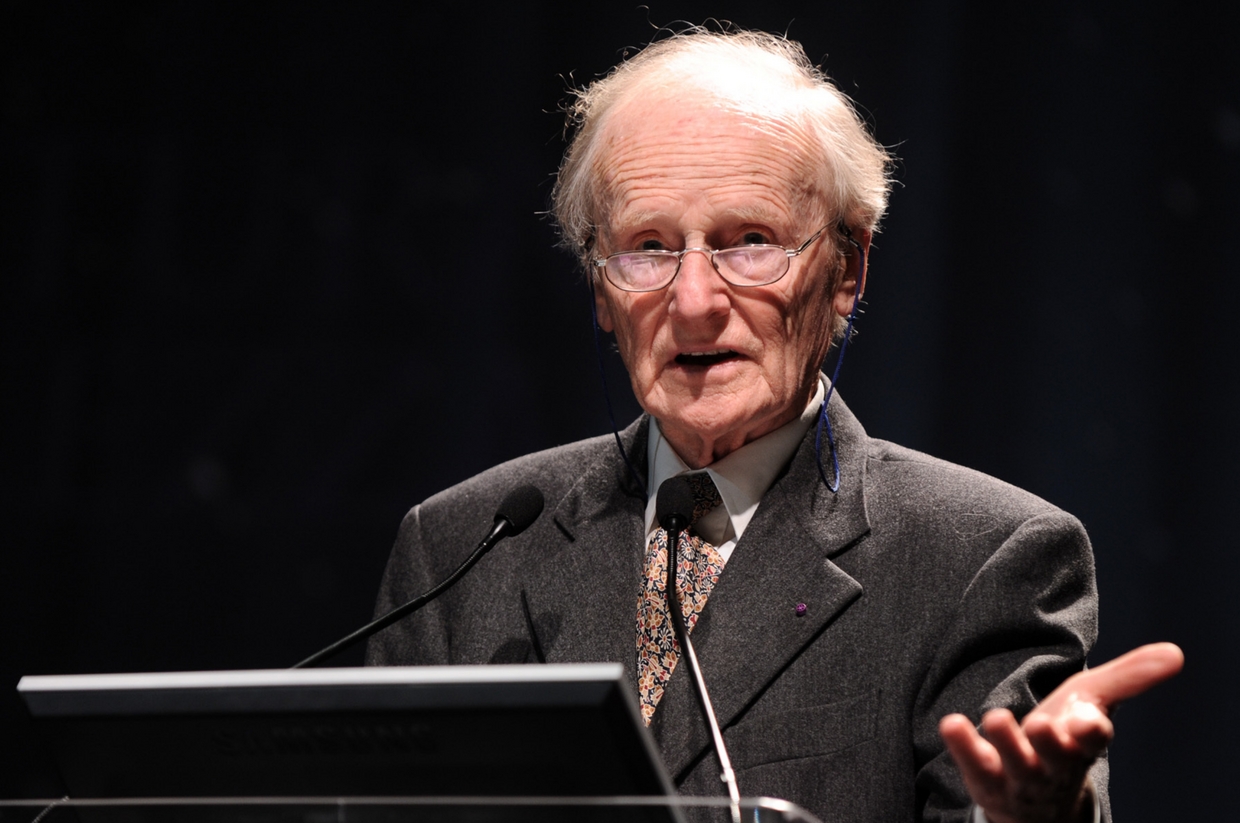

Robert Spaemann is a German Catholic philosopher (1927–2018) known for his work on ethics and political philosophy. I took classes with him when he was still teaching in Munich, and I was impressed and also skeptical about his resurrection of the concept of Teleology. In recent years I returned to study his philosophy again, and developed an interest in his view on political philosophy.

In his later work, Spaemann develops a philosophy of the person that can also serve as a justification for Human Rights. “Persons: The Difference Between ‘Someone’ and ‘Something’” (“Personen: Versuche über den Unterschied zwischen ‘etwas’ und ‘jemand’”). In this book, Spaemann explores personhood, ethics, and the role of community and tradition in our pursuits of a good life. These themes naturally invite a dialogue with Rousseau, who tackled similar issues from different perspectives. In the following, I want to summarize Spaemann’s reflections on Jean-Jacques Rousseau. He uses Rousseau’s ideas to elucidate and critique various aspects of Enlightenment thought, autonomy, and community. While Rousseau serves as an important reference point, he is not the central focus of the book. However, the engagement with Rousseau provides valuable insights into Spaemann’s larger philosophical and political framework.

As a Catholic thinker, he is critical of the Enlightenment slogan of liberation through reason alone. Does this not align him with Rousseau, who was an early critic of the Enlightenment? The picture is mixed. Spaemann has a nuanced view of Jean-Jacques: Rousseau’s critique of Enlightenment rationalism and his emphasis on human emotion resonates with Spaemann’s own beliefs, but he disagrees on the role of tradition and religion in society.

Rousseau (1712-1778) is a strong critic of social inequality and a proponent of the “noble savage” concept – the idea that the human being is inherently good, but is corrupted by society. His work laid some of the ideological groundwork for the French Revolution.

In contrast, Spaemann’s political thought is profoundly shaped by his commitment to the Catholic tradition, which places a high value on social continuity, religious authority, and a vision of the common good that is, in part, transcendent. For Spaemann, this tradition is not a burden, but a treasure trove of wisdom, providing orientation and stability to communities. Whereas Rousseau’s idea of the “general will” (Volonté générale) leans toward a form of direct democracy and radical equality, Spaemann cautions against the tyranny of majoritarianism and underlines the importance of mediating structures like family, church, and small communities.

The political narratives of both philosophers can be seen as a quest for authenticity—Rousseau seeks it through the lens of a pre-civilized state of nature, while Spaemann envisions it through engaging with and enriching existing traditions. Spaemann admired thinkers like Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas, and he saw in Rousseau an important interlocutor, but ultimately one who proposes a ‘false innocence’ by turning his back on the complexity and depth that tradition offers.

Rousseau’s secular humanism and his notion of “civil religion” stand in contrast to Spaemann’s belief in the necessity of divine law as a foundation for ethical reasoning. While Rousseau thought that religious doctrines could be subordinated to the dictates of reason and the common good, Spaemann argued that this amounted to the destabilizing relativism that surrounds us today. He insisted that religion, particularly Catholicism, offers an irreplaceable moral compass.

The emotional strength of Rousseau’s call for natural freedom and equality struck a chord with Spaemann, but he saw that the consequence of embracing Rousseau’s ideas fully would be the loss of those traditions and institutions that lend life its richness and moral texture.