When presented in the West as gentle exercise for seniors or moving meditation, Tai Chi reveals only its surface. Its full name – Taijiquan, “Supreme Polarity Fist” – points to an embodied philosophical system that translates the cosmology of Song dynasty Neo-Confucianism into a system of human body movements. To practice Tai Chi is to physically investigate the nature of reality itself, transforming metaphysical diagrams into lived experience and making oneself a conscious participant in the creativity of the universe.

The Cosmological Background

The philosophy begins not with movement but with stillness. Zhou Dunyi‘s eleventh-century Taijitu shuo (Explanation of the Diagram of the Supreme Polarity) presents reality as a processual unfolding: from Wuji, the “Non-polar” state of pure, undifferentiated potential, emerges Taiji, the “Supreme Polarity” or “Great Ultimate.” This first stirring gives rise to movement and stillness, which in turn generate yin and yang – the complementary opposites whose ceaseless interplay produces the Five Phases (wood, fire, earth, metal, water) and ultimately the ten thousand things of the manifest world.

This is not merely abstract cosmology. For Zhou Dunyi and his successor Zhu Xi, the pattern (li) that structures the cosmos equally structures human nature. The universe is not a static object but a dynamic, creative process, what the tradition calls “the great transformation,” and humanity stands at its apex. As Zhou writes, “Only humans receive the finest and most spiritually efficacious qi.” We are the point at which cosmic creativity becomes self-aware, capable of consciously participating in the patterns that brought us into being.

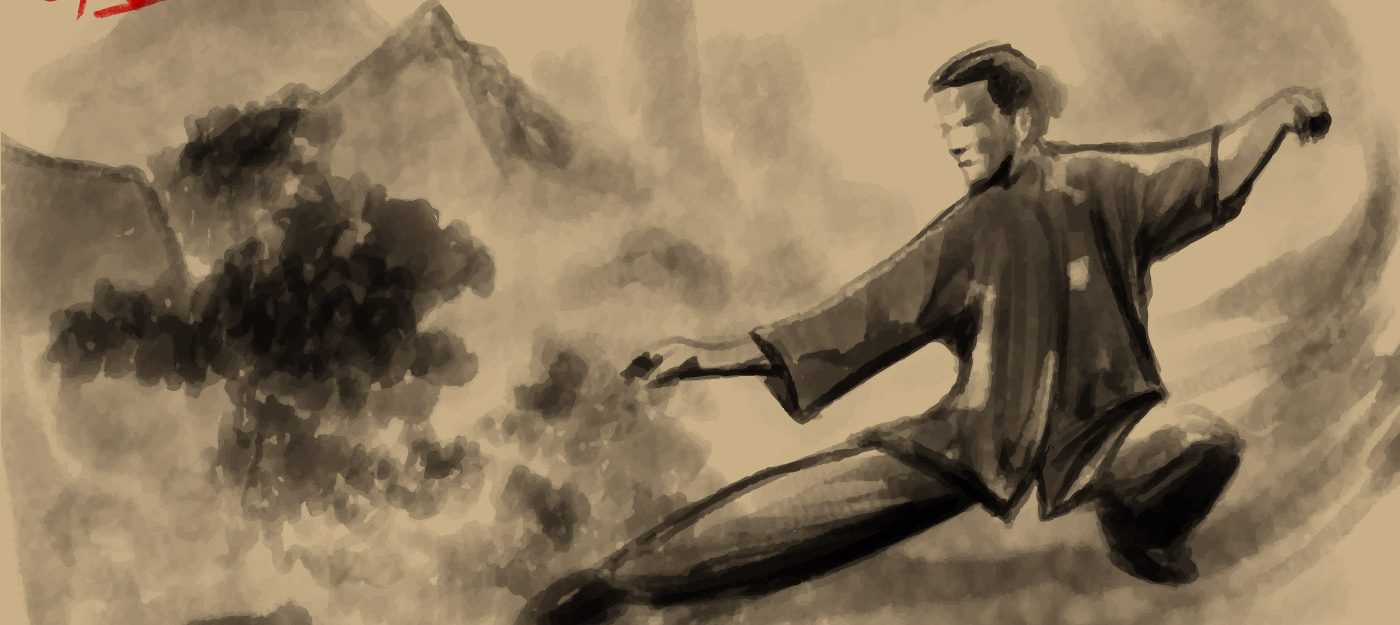

Taijiquan translates this vision from metaphysics into movement, from diagram into dance.

From Chenjiagou to the World: A Living Transmission

The art’s documented history begins in seventeenth-century Chenjiagou, a village in Henan province, where Chen Wangting (1580–1660), a retired Ming military officer, is credited with synthesizing boxing methods, therapeutic exercises (daoyin), breath cultivation (qigong), and military drill into the routines that would become the Chen family style. Yet the practice drew on far older roots: the Mawangdui silk manuscripts sealed in 168 BCE depict forty-four therapeutic postures; texts like the Neiye (“Inward Training,” fourth century BCE) already articulated breath regulation and mind-body alignment; and the Huangdi Neijing (compiled between the first century BCE and first century CE) provided the medical vocabulary of qi, yin-yang balance, and preventive cultivation that Tai Chi would translate into pedagogical method.

The art remained largely within the Chen family until Yang Luchan (1799–1872) studied in the village and later taught in Beijing, where his large-frame, even-tempo approach made the practice accessible beyond martial specialists. His grandson Yang Chengfu (1883–1936) systematized the form and articulated the famous “Ten Essentials”—not ten techniques but ten norms of attention that guide the practitioner toward relaxed wholeness, sensitivity, and continuity. Meanwhile other masters developed parallel lineages: Wu Yuxiang’s small-frame precision, Wu Jianquan’s upright structure, Sun Lutang’s integration of stepping patterns from Xingyiquan and Baguazhang.

In 1956, a state-backed committee compiled the twenty-four-posture Simplified Form to democratize the practice, creating the six-minute routine now performed in parks worldwide. UNESCO’s 2020 inscription of Taijiquan as Intangible Cultural Heritage recognized both its depth and its remarkable capacity to travel—to remain philosophically coherent even as it adapted to new contexts, cultures, and practitioners.

The Body as Laboratory

Every Tai Chi form begins with the Wuji posture: standing still, feet together, arms at the sides, silent and empty. This is the physical embodiment of the Non-polar, the state before differentiation. The first movement—a slow raising of the arms or stepping forward—marks the transition from Wuji to Taiji. In that single, initial motion, undifferentiated unity gives way to the world of duality, and the dance of yin and yang begins.

The practice is a continuous, seamless flow between complementary opposites. As weight shifts from one leg to the other, one becomes “full” (substantial, yang) and the other “empty” (insubstantial, yin). Movements expand outward and contract inward; the breath follows, exhaling on expansion, inhaling on contraction. The body is in constant motion, yet the practice demands profound internal stillness of mind, what Zhu Xi called the foundation from which proper activity arises. Tai Chi is famously soft, but it cultivates a dynamic softness that can absorb and neutralize incoming force (yin) before issuing a powerful strike (yang), embodying the principle that each pole contains the seed of its opposite, as shown by the dots within the familiar Taiji symbol.

Beyond yin and yang, the Five Phases structure the art’s strategic vocabulary. The primary movements correspond to these elemental energies: advance (fire), retreat (water), look left (wood), look right (metal), central equilibrium (earth). These are not arbitrary labels but a system for understanding how to transition fluidly between different qualities of action in response to changing circumstances. The eight core methods—peng (ward-off), lü (rollback), ji (press), an (push), cai (pluck), lie (split), zhou (elbow), kao (shoulder)—together with the five steps form what the tradition calls the Thirteen Postures, a grammar of movement that practitioners drill in partner exercises (push-hands) to develop what the texts call “listening energy” (tingjin): the ability to detect change at the threshold where movement turns into stillness and answer it with minimal necessary action.

Self-Cultivation Through Embodied Investigation

For Zhu Xi, self-cultivation involved the “investigation of things” (gewu)—a rigorous intellectual and moral effort to perceive the Principle (li) within all phenomena and purify one’s own Vital Force (qi). Tai Chi offers a parallel, embodied path to the same goal. Instead of studying only the classics, the practitioner studies the principles of the universe through sensations of balance, momentum, and energy flow. The form becomes a text; the body becomes both laboratory and scripture.

Yang Chengfu’s Ten Essentials provide the investigative method: suspend the crown lightly; contain the chest and raise the back; relax the waist; distinguish full and empty; sink shoulders and drop elbows; use intent (yi) rather than brute force (li); coordinate upper and lower; harmonize internal and external; maintain continuity without breaks; seek stillness within movement. These are not ten separate techniques but a single integrated awareness, what the tradition calls “reverent composure” (jing) in motion. To perform the movements correctly requires complete presence, attention free of distraction, the mind calm and reflective as still water, allowing the body to respond to the principles of movement with perfect spontaneity.

This is how the practice aims to overcome what Zhu Xi called the “turbidity” of one’s physical nature, allowing one’s pure, original nature to manifest effortlessly. The slow, deep breathing and coordinated movements are designed to cultivate and circulate internal energy, breaking down blockages and unifying mind and body. What begins as deliberate effort gradually becomes natural responsiveness: the highest skill being not to impose one’s will but to listen, harmonize, and redirect with minimal intervention, like water flowing around obstacles.

Conscious Participation in Cosmic Creativity

When you practice the form, you do more than exercise. Your body becomes a microcosm, re-enacting universal patterns of creation: the shift from emptiness to existence, the endless cycling of yin and yang, the balancing of elemental forces. The practitioner does not impose will on the world but learns to listen and harmonize with its underlying currents. The ultimate skill in Tai Chi’s martial application is not to meet force with force but to sense an opponent’s energy, yield to it, blend with it, and redirect it effortlessly — a physical metaphor for the sage’s relationship with the Dao, acting in perfect harmony with the flow of reality, achieving great things with minimal effort.

Tai Chi is a practice where the human being participates in the creativity of the universe. The cosmos creates humanity, and humanity, through practices like Tai Chi, consciously and artfully expresses the principles of the cosmos, completing the circuit of creativity. We are not alien spectators but the universe’s consciousness, the point at which the great transformation becomes self-aware.

In this sense, Tai Chi is not esoteric power but disciplined sensitivity. It prompts us to learn to inhabit our original nature with such clarity that action arises without force, stillness pervades movement, and the ten thousand things of daily life become occasions for practicing the Dao. It is philosophy you can feel, cosmology you can live, a way of fulfilling what Zhou Dunyi called our unique endowment, the finest qi, by consciously aligning our own life-force with the great life-force of reality itself. That depth, more than mythology or health benefit, is why Taijiquan has traveled so well and why its promise remains as vital today as when those first practitioners stood in Wuji posture, preparing to step into the dance of being.