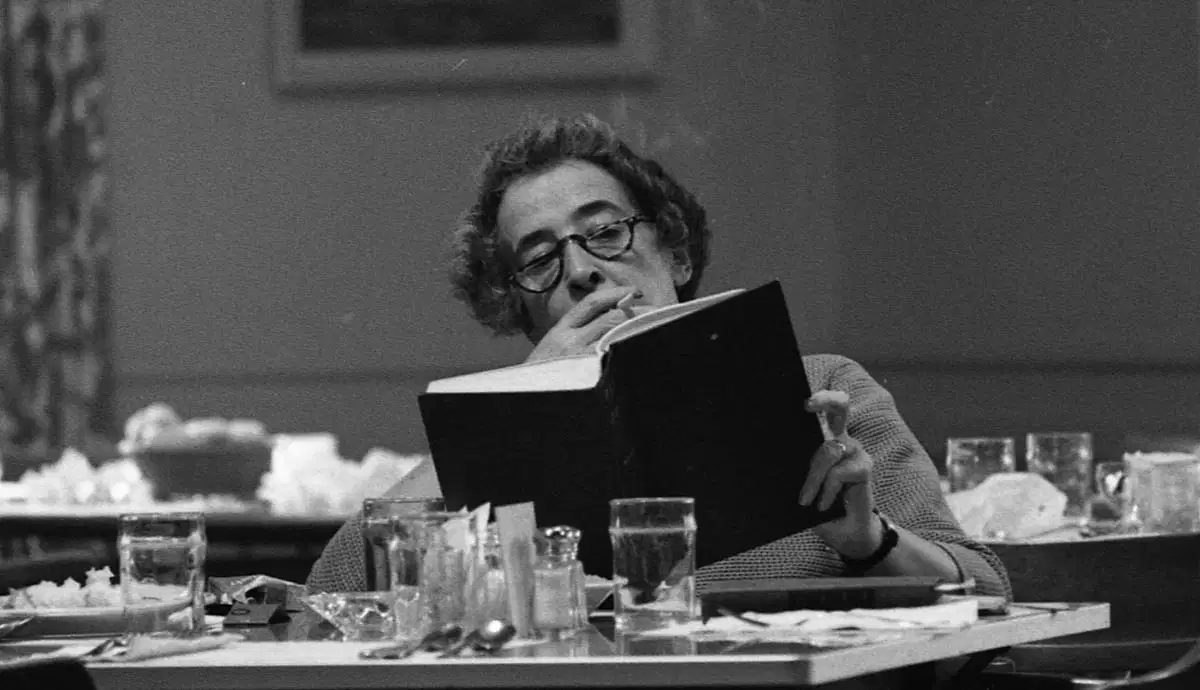

Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) was an original and very clear-sighted political philosopher in the twentieth century. Her work, emerging from the experiences of totalitarianism and exile, offers a distinctive vision of political life that continues to be relevant for our contemporary challenges to democracy and human dignity. This post explores Arendt’s central contributions to political thought, focusing on her analysis of totalitarianism, her conception of the public sphere, and her understanding of judgment and moral responsibility. (Here is a link to an interview)

Origins in Crisis

Arendt’s intellectual journey was shaped by her experiences as a German Jew. Forced to flee Nazi Germany in 1933, she worked with Jewish refugee organizations in Paris before immigrating to the United States in 1941. These biographical details are not incidental to her philosophy but foundational to it. The rise of totalitarianism in Russia, China, and Germany – which she witnessed firsthand – became a central problem her work sought to understand and address.

Her first major work, “The Origins of Totalitarianism” (1951), analyzed the unprecedented nature of totalitarian regimes. For Arendt, totalitarianism represented not merely another form of tyranny but something radically new: a system that sought to eliminate human spontaneity and plurality through terror and ideology. By reducing humans to “bundles of reactions,” totalitarian systems aimed to make people “superfluous” in the emerging culture of the masses. This destruction of human plurality constituted what she initially called “radical evil” – evil that could not be explained through traditional concepts of self-interest or utility. This leaves the perpetrators, Mao, Stalin, and Hitler, as well as their closest collaborators, in a new kind of category: they are the agents of evil in ways we have not seen before.

The Human Condition and the Vita Activa

In “The Human Condition” (1958), Arendt developed a framework for understanding human activity that distinguished between labor, work, and action. Labor concerns the biological necessities of human existence; work creates the durable artifacts that constitute our shared world; action, which for Arendt is the highest form of human activity, consists in the free engagement of citizens in public life. Unlike labor and work, action reveals the unique identity of each person and requires a plurality of perspectives to flourish.

Arendt’s emphasis on action reflects her core political values: freedom, plurality, and natality (the human capacity to begin something new). For her, politics properly understood is not about domination or administration but about collective freedom exercised in a public space. This conception stands in opposition to modern tendencies that reduce politics to power, economics, or bureaucratic management.

The Banality of Evil

Arendt’s reporting on the trial of the Nazi Adolf Eichmann, published as “Eichmann in Jerusalem” (1963), introduced the controversial phrase “the banality of evil.” Contrary to many misinterpretations, Arendt did not minimize Eichmann’s crimes or deny his anti-Semitism. Rather, she observed that evil deeds of monstrous proportion had been committed by someone who appeared not as a demonic villain but as a thoughtless bureaucrat. This thoughtlessness—the inability to think from the standpoint of others—was, for Arendt, closely connected to moral failure.

This experience led Arendt to revise her conception of evil. Rather than being “radical,” evil could be “banal” in its origins—arising not from depth but from shallowness, from failure to engage in the activity of thinking. This insight connects to her later explorations of thinking and judgment in “The Life of the Mind,” which she was working on at the time of her death in 1975.

Citizenship and the Public Sphere

Central to Arendt’s political vision is her conception of citizenship as active participation in a shared public world. For Arendt, public space is both the space of appearance, where citizens can disclose who they are through speech and action, and the common world that provides stability and context for human affairs. This public realm is artificial rather than natural, created through human action and preserved through institutions and memory.

Arendt emphasized the distinction between public and private realms, criticizing the modern rise of “the social”—the extension of private concerns like economics into the public sphere. This is not surprising, because she grew up in a more conservative climate in Germany, and studied in Freiburg as a student of Heidegger. Marxist thinking is not close to her, so her insistence on this separation between private and public has drawn criticism, particularly from those who see it as excluding important issues of social justice from political consideration.

Judgment and Political Responsibility

In her late work, Arendt turned increasingly to questions of judgment and responsibility. Drawing on Kant’s aesthetics, she developed a theory of political judgment that emphasized enlarged thinking—the capacity to consider multiple perspectives beyond one’s own. This ability to think representatively is essential both for moral autonomy and for genuine political deliberation.

For Arendt, judgment operates in tension with truth. While factual truth is essential to political life, rational truth, the truth asserted by judgement, which claims absolute authority, can actually undermine the plurality of perspectives that politics requires. Political judgment must navigate between relativism and dogmatism, finding validity through the process of forming representative opinions that incorporate multiple standpoints.

Relevance Today

Arendt’s political philosophy cannot be categorized easily. She does not fit into any school, she is an acute observer of social life, she thinks politically, and she understands the role of power in politics. She was critical of liberalism, and deeply committed to constitutionalism and the rule of law. Though she valued tradition, she rejected appeals to ethnic or religious identity as the basis for political community. She would certainly not have been in favor of identity politics or “critical race theory.” Her work inhabits the tradition of civic republicanism, emphasizing active citizenship, public deliberation, and political freedom.

In our contemporary situation, marked by challenges to democratic institutions and the reemergence of authoritarian tendencies, Arendt’s insights remain urgently relevant. Her analysis of totalitarianism helps us recognize dangerous political patterns; her emphasis on plurality reminds us that democracy requires engagement with diverse perspectives; her exploration of thoughtlessness and evil warns us against moral complacency. Above all, her vision of politics as a realm of freedom and new beginnings offers hope that collective action can interrupt the seemingly inevitable recurrent rise of authoritarianism and open new possibilities for human flourishing.

Arendt’s legacy is anchored in the tradition of Aristotle and Plato: She invites us to think about politics not as a necessary evil or a technical problem but as the highest expression of our humanity – the space where we appear to one another in our distinctness and create a common world through speech and action. In a time of political cynicism, this vision of politics as the realm of freedom, meaning, and human dignity remains her most powerful contribution.